The Training Power of VR Shotgun Tech

with Clay Hunt VR & Real Stock Pro

Step aside, gimmicky games and pixelated bird hunts—VR shotgunning is here, and it’s incredible! Virtual Reality (VR) has evolved into an immersive experience, and it’s taking the shotgun sports by storm. Today’s shotgun simulators don’t just entertain—they educate, train and thrill with uncanny realism. From the avid upland hunter warming up for the season, the total beginner wondering what it feels like to track a clay across the sky or the competition shooter squeezing in extra practices, VR is an innovative way to hone skills, experience the thrill of shotgunning and train like never before. No shells to buy, no recoil to endure and no need to wait for perfect weather—just focused practice, real-time feedback and a surprisingly addictive way to sharpen shooting skills.

Two companies are leading the charge in VR shotgunning, creating products that make the experience feel as close as possible to the real world. Combining the power of Clay Hunt VR (shotgungaming.com/clayhuntvr) software with the realistic feel of a Real Stock ProTM V3 proxy shotgun stock (texturevr.com) pulls you into the digital realm. Your mind does the rest. How real does it feel? While testing the system on sporting clays, I broke an overhead target. Virtual target fragments rained down. Embarrassingly, I ducked to prevent getting hit. Of course, I didn’t…but my brain was convinced I was on a sporting clay range.

Why Virtual?

Before diving into the product details, it’s worth exploring the benefits (and a few drawbacks) of VR for shotgun practice and training.

Honestly, I’d initially dismissed the technology as nothing more than an elaborate video game. However, huddled in my house on a -30°F night, the idea of realistic shooting from the comfort of my living room was inviting. I also daydreamed of staying cool during the dog days of summer. Would I enjoy year-round, climate-controlled practice? Yes!

In a digital world, anything is possible. Switching between trap, skeet, sporting clays and simulated game hunts is easy, allowing you to try new sports. The software allows customized gameplay that provides increasing challenges in a variety of environments.

VR shooting provides a safe environment for practice. Without live ammunition or actual firearms, there are no safety risks. It is perfect for everyone, especially beginners. Some VR headsets establish a secure boundary for the virtual range, so there’s no bumping into the coffee table during practice.

Realistic target engagement delivers lifelike clay target and game-hunting scenarios. In the virtual world, high-definition graphics mimic real-world shooting dynamics. Immediate feedback provides detailed analytics on tracking, reaction time, follow-through and hit patterns. This enables precise, data-driven skills improvement. Further, the VR headset’s view can be shared with another screen in real-time to analyze and help correct errors.

VR is a cost-effective way to squirrel away money (for a new shotgun) while becoming a better shooter. After an initial investment, there is no need to buy ammo or clays. An ability to practice more and spend less is a win in anybody’s book.

Practice. Practice. Practice. It’s the mantra of dedicated shooters. VR improves focus and builds “muscle memory.” VR also reinforces proper shooting form, improves target tracking, reaction times and decision-making skills. After-the-shot analytics provide instant feedback.

Teams and individuals can simulate competition under pressure. And, because it’s online, shooters can be located anywhere in the world. Urban and remote users can train without traveling. Hunter education programs benefit from introducing shotguns to students.

VR encourages participation from new demographics, creating a low-barrier entry. For shotgun clubs and hunting lodges, it provides a source of entertainment and camaraderie.

Are there drawbacks? Sure. VR shotgunning lacks recoil, which is both good and bad. It’s less realistic. But with no recoil, it allows you to focus on the fundamentals and transitions without distraction. Screentime dominates our lives, and VR is another screen. Finally, the controller trigger doesn’t feel like a real gun trigger, but that’s less important than you may think.

Clay Hunt VR

At the heart of my virtual shotgunning experience is the Clay Hunt VR app. Once downloaded to my MetaQuest 3 headset, I clicked the game icon and was instantly transported to a rustic hunting lodge, the virtual home base for clay shooting and hunting. As a newbie to VR technology, I was mesmerized by this digital world: a 360° spectacle of details. On the main “wall” is the game menu—portals to the trap, skeet and sporting clays ranges as well as access to target-rich hunting spots for ducks, pheasants, doves and more.

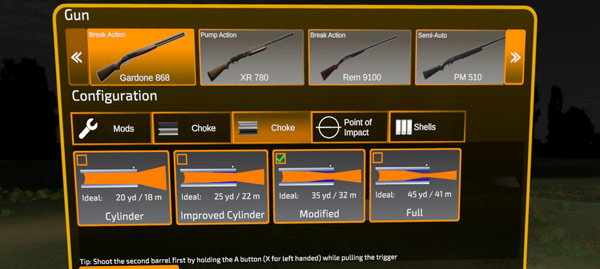

The software’s rich feature set includes options for shotgun type, barrel length, rib height, choke and load (shot type, size and velocity) and more. All these details and variables, like wind, add to the realism.

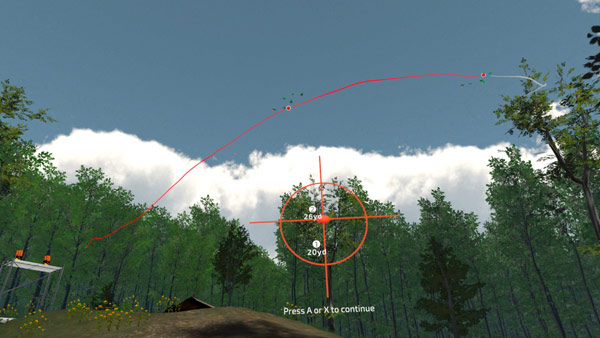

Clay Hunt VR has game modes for all skill levels. Starting at beginner difficulty, slower targets and more forgiving hit recognition build confidence while teaching the fundamentals. The app displays an aim trace and a shot pattern, which is invaluable for self-directed learning. The analysis also shows the pattern density illustrating shotgun ballistics. Experimenting with chokes, loads and shotgun options all provide valuable lessons without expensive ammo.

As skills develop, you can move up to professional difficulty with accurate physics and target speeds. I tested this by calling my shots, and everything seemed spot-on.

Clay Hunt VR is a terrific coaching tool. The screen can be displayed (cast) live to another device like a TV or phone, allowing others to see what the shooter does. Coaches can view, correct issues and provide advice. For example, my son chose a difficult sporting clays presentation. I watched him struggle to hit the target. With a bit of coaching, he connected and then consistently crushed the target several times after.

By using the onscreen analysis, we both learned from the session. The coolest part about Clay Hunt VR is the ability to make micro adjustments, changes that advance shooting outcomes. In the real world, it’s simply a hit or a miss. In the game, I added (or decreased) lead little by little until I was dialed in.

Shotgun Gaming Oy developed the simulator to be as realistic as possible. Software development is ongoing with improvement driven by an active community of more than 6,000 members in the private Facebook group and 1,400+ members in the Clay Hunt VR Community Discord.

The REAL STOCK PRO V3 Advantage

While Clay Hunt VR can run with only Meta Quest controllers, without a VR shotgun stock, it’s only a game. The power of the pixels comes from using a dedicated stock, one that fits and feels like a real shotgun.

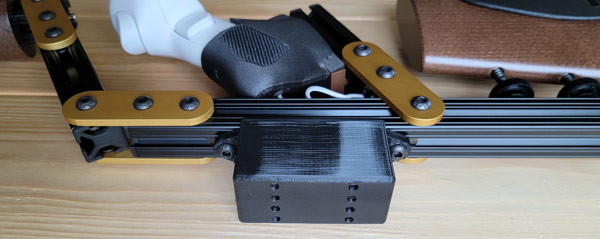

The Real Stock Pro V3 by TextureVR is designed to replicate the feel of a real shotgun as closely as possible in VR. In the hand, it looks futuristic, but when configured right, it truly feels like a real shotgun, but not just any gun, your shotgun! In VR, my brain connects the (virtual) dots.

The Real Stock Pro features real wood for the stock and forend, providing a natural feel, high-quality hardware for adjusting the stock geometry and 3-D printed parts for precise controller fit. There is so much adjustability that the stock can be configured to fit most body types and shooting styles. The V3 black series stock also includes a weight kit.

Real Stock Pro V3’s length of pull (LOP), distance between the stock and forearm and various angles are easily adjusted with an included hex wrench. The weight and balance can be customized up to 10 lbs. in 1 oz. increments to feel the same as a specific make and model. It let me experiment with different configurations until it felt right.

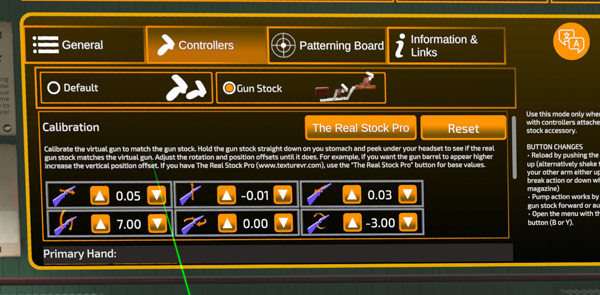

VR shotguns differ from real ones in fit, sensitivity and shot precision. Minor physical adjustments (like cast and drop) don’t translate the same way as they do in real life due to the proximity of the VR controllers. I found that setting the Real Stock Pro’s correct (fitted to me) length of pull, comb height, trigger position and forearm placement is essential, while drop, cast and alignment down the VR “barrel” are best adjusted in-game. When it feels right in the shoulder and ‘looks’ right in the game, it’s 100% believable that you’re shooting a shotgun. The Real Stock Pro features thumb screws to quickly adjust LOP and riser height, which is handy when sharing the stock with different-sized shooters.

Inside Clay Hunt VR, the patterning board area is where you can verify and adjust the Real Stock Pro’s VR sight picture against the real one, as we discussed. It also lets you tune the point of impact (POI). In VR, I adjusted until I had a centered 50/50 pattern. Once set, the pattern is easily adjusted in the settings’ menu for desired POI, such as 60/40 for skeet, 80/20 for trap and 50/50 for sporting clays and hunting or whatever I wanted.

After setup, the Real Stock Pro perfectly replicated my shotgun. By practicing mounting and watching the aim trace in the game, I improved my consistency, swing and follow-through.

Because the stock fits perfectly and feels natural, I asked friends and family to monitor my mounting technique, cheek weld, swing and other specifics while I practiced. Their feedback was invaluable.

Using the Real Stock Pro with Clay Hunt VR transforms the system from a game to a powerful shotgun training tool. The synergy of these two products is an outstanding training tool; one without the other is pointless.

Back to Reality

From clay to code, VR is changing the way we shoot. Within the first 24 hours, I logged more than 1,000 shots and didn’t have a sore shoulder!

There’s a saying that “Practice doesn’t make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect.” Clay Hunt VR and Real Stock Pro V3 take shotgun practice to the next level, both figuratively and literally. An exact fit and precise analysis in VR provides the desired “perfect practice.”

I love the VR experience, and while it will never replace the sights, sounds and smells of the outdoors, it is an unquestionably valuable training tool. The VR experience is also entertaining, so when you’re ready to have some fun, through a friendly competition or a virtual hunt, the gaming aspect feeds that side, too.

Don’t just take my word for it. Clay Hunt VR has an average 4.8-star online review, and the comments about the Real Stock Pro are overwhelmingly positive. Join the growing community of VR shotgunners and harness the power of VR technology.

Let’s level up — my headset is fully charged, so it’s time to grab my Real Stock Pro “shotgun” and head to the Clay Hunt VR “range.” See you online! SS

Lowell Strauss was born and raised in Saskatchewan, Canada. Each fall, he heads to the field in search of waterfowl and upland birds. In the off-season, look for him at the range testing shotguns and honing his wingshooting skills, in the field handling his yellow Lab or at the bench building the perfect handload. Lowell has won numerous national and international awards for his writing and photography.